I suppose it's fairly fitting that when I first tried to watch Dhobi Ghat, I was late and then, about 15 minutes into the film, the projector broke down. Over a year later, I finally get the film on DVD and begin watching again. The back of the DVD contains a lie: I'm watching a 97 minute film, expecting it to be roughly 178 minutes. So it's all a weird, splintered experience - first I just got a glimpse, and when I was finally getting into the characters, the projector died. Then I anticipated a longer story, and when the ending credits came up, I stared, puzzled, at my TV.

Of course, not the first time the back of the DVD has lied to me. Won't be the last, either.

Dhobi Ghat is a portrait of Mumbai, and four people in it. For a portrait of a city that at least has the appearance of constantly being in motion, this portrait is strangely still. A lot of time is spent on just surveying surroundings. A lot of it feels like that amazing cup of coffee on a Sunday morning that you sip, safe in the knowledge you don't have to be anywhere that day; you can just be. It's a languid film.

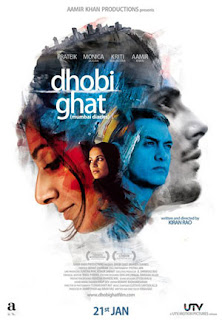

I certainly liked it, but I've yet to determine precisely how much. I enjoyed the way the four characters were varied - from the poor dhobi (washer) Munna played by Prateik, to the ultra-rich, educated NRI Shai (Monica Dogra), as this showed the dramatically different sides of the city. The jobs that Shai only sees as a sort of exotic tourist attraction that would make for good photographs, Munna actually does.

At first I thought about writing something about economic privilege and how it colours the film, and how it perhaps doesn't try to highlight the problematic aspects of it. Upon further thought, however, I realised it rather does, but the way it's portrayed, can be subtle. After scenes where Shai has begun to treat Munna as more of a friend, not a servant, we see him interact with Arun (the artist character played by Aamir Khan). To him, Munna's merely a servant. The difference hits the viewer uncomfortably in the face, even though Arun doesn't mean anything by it - it's just how things are. But the privilege of Shai doesn't disappear just because her and Munna get close. In fact, it only further highlights it.

While I was most fascinated by the story of Arun discovering the tapes of Yasmin (Kriti Malhotra), a middle-class housewife, brand new to marriage, the Shai-Munna story was much more revealing. Shai is basically the kind of character who in a different film would probably be the Bollywood heroine who'd eventually tone down her brat-like behaviour and become a Good Indian Woman for the hero to marry. In this film, however, you see her making choices that are frankly morally questionable. But she sails through life, where other people would run into bumps in the road, because of her privilege.

I want to say that the film achieved its goal, as it made me think about all of these things and more, but then I wonder - perhaps it had a more modest goal, of just throwing together some characters without flagging up that many questions in the viewer. As a debut film for director Kiran Rao, I wouldn't say it's impressive - it's well-made, and it's promising. I hope she delivers on some of that promise.